How Many Calories in a Teaspoon of Sugar – Granulated sugar represents the most common sweetener found in sugar bowls and restaurant packets worldwide. This refined sugar differs markedly from unrefined or partially processed alternatives like raw brown sugar.

Understanding the nutritional content of sugar enables accurate calorie counting, supports weight management efforts, helps control blood glucose levels, and facilitates informed dietary choices. These empty calories provide no essential nutrients, vitamins, or minerals to support bodily functions.

This comprehensive article will analyze the detailed macronutrient composition of various sugar types, compare caloric density between natural sweeteners and artificial alternatives, evaluate the health impacts of sugar overconsumption on cardiovascular health, metabolic function, and dental wellness. We’ll also explore hidden sugars in processed foods, examine the food industry’s role in promoting sugar consumption, and provide practical strategies for effectively reducing added sugar intake.

II. Detailed Nutritional Profile of Granulated White Sugar

A. Macronutrient Composition

Granulated white sugar (table sugar) maintains high energy density at 387 calories per 100 grams, placing it among high-energy foods. Its composition remains simple: 100% carbohydrates, 0% fats, and 0% protein. This makes granulated sugar a pure carbohydrate source, providing rapid glucose for cellular energy production.

Each teaspoon (approximately 4.2 grams) contains:

- 16 calories

- 4.2g total carbohydrates

- 4.2g total sugars

- 0g dietary fiber

- 0g protein

- 0g fat

B. Additional Nutritional Components

White sugar contains no sodium, cholesterol, or dietary fiber. This explains why nutritionists classify calories from refined sugar as “empty calories” – they provide energy while lacking essential micronutrients necessary for optimal health.

Sucrose comprises the primary component in table sugar, accounting for the entire 4.2g in each teaspoon. This compound consists of one glucose molecule and one fructose molecule bonded together. The metabolic breakdown of sucrose occurs rapidly in the body, leading to quick blood sugar elevation.

C. Glycemic Index (GI) and Glycemic Load (GL)

White sugar’s Glycemic Index measures 65, categorizing it as a medium-GI food. This number indicates refined sugar’s ability to raise blood glucose levels relatively quickly after consumption. However, one teaspoon’s Glycemic Load equals only 3, calculated by multiplying GI by carbohydrate content then dividing by 100.

This low GL explains why a small portion like one teaspoon sugar has relatively minimal impact on blood sugar response. Problems arise when cumulative intake from multiple servings throughout the day, especially from sweetened beverages and processed foods, accumulates.

III. Various Sugar Types and Alternative Sweeteners

A. Detailed Nutritional Analysis of Natural and Processed Sugars

1. Brown Sugar

Brown sugar contains 16 calories per teaspoon, exactly equivalent to white sugar in energy content. Its composition includes refined white sugar coated with molasses, creating distinctive color and subtle flavor differences.

Brown sugar’s nutritional advantage over white sugar remains minimal. Molasses content provides trace amounts of calcium and iron, but these quantities prove too small to create meaningful nutritional benefits. Raw sugar and turbinado sugar fall into similar categories regarding caloric value.

2. Honey

Honey provides 21 calories per teaspoon, 31% higher than table sugar. This natural sweetener, produced by honeybees from flower nectar, contains a complex mixture of fructose, glucose, and trace compounds.

Honey’s antioxidant properties, particularly flavonoids and phenolic acids, offer potential health benefits. Raw honey’s antimicrobial activity has been documented in numerous studies. However, higher fructose content (approximately 38-40%) may impact liver metabolism differently than sucrose.

3. Maple Syrup

Pure maple syrup contains 17 calories per teaspoon and is extracted from maple tree sap. Its nutrient profile includes trace minerals like zinc and manganese, along with antioxidant compounds.

Minimal processing methods preserve more natural compounds compared to refined sugars. Mineral content, though small, still contributes partially to daily micronutrient intake.

4. Coconut Sugar

Coconut palm sugar provides 15-16 calories per teaspoon, equivalent to white sugar. The extraction process from coconut palm sap creates a product with lower glycemic index (35-54) compared to regular sugar.

Lower GI means coconut sugar causes slower blood glucose elevation, potentially beneficial for individuals with insulin sensitivity concerns. Trace minerals like potassium, zinc, and iron are also present in small amounts.

B. Non-caloric/Low-calorie Sweeteners (Artificial/Non-caloric Sweeteners)

Alternative Sweetener Comparison Table

| Sweetener | Calories/tsp | Sweetness vs Sugar | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stevia | 0 | 200-300x sweeter | Stevia plant leaves |

| Erythritol | 0.8 | 60-70% as sweet | Glucose fermentation |

| Monk Fruit | 0 | 150-200x sweeter | Luo han guo fruit |

| Sucralose | 0 | 600x sweeter | Chemical modification of sucrose |

| Aspartame | 4 | 200x sweeter | Amino acids |

Natural sweeteners like stevia and monk fruit extract are FDA recognized as Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS). Artificial sweeteners like sucralose and aspartame also pass extensive safety testing protocols.

IV. Sugar’s Impact on Health

A. Benefits of Sugar (When Consumed in Moderation)

Quick energy provision serves as sugar’s primary function in human physiology. Glucose acts as the preferred fuel source for brain cells, red blood cells, and muscle tissue during high-intensity exercise. Liver glycogen storage from carbohydrate intake, including sugars, provides energy reserves during fasting periods or increased metabolic demand.

Sugar’s food processing applications extend beyond sweetening. Fermentation processes rely on sugars to produce bread, yogurt, and fermented beverages. Sugar acts as a preservative in jams and jellies, extends shelf life of baked goods, and enhances texture in numerous food products.

B. Adverse Effects of Sugar Overconsumption

1. Weight Gain and Obesity

Excessive sugar intake, particularly from sugar-sweetened beverages, contributes significantly to weight gain and abdominal adiposity. Liquid calories from sodas, fruit drinks, and flavored coffees don’t trigger satiety mechanisms effectively, leading to overconsumption.

USDA American sugar consumption data shows declining trends in recent years, but average intake remains well above recommended levels. Visceral fat accumulation from chronic sugar overconsumption increases risks of metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular complications.

2. Increased Type 2 Diabetes Risk

High sugar diets overwhelm pancreatic beta cells, leading to insulin resistance development. Fructose metabolism in the liver bypasses normal glycolytic regulation, potentially contributing to hepatic insulin resistance.

Detailed Biological Mechanisms: Fructose undergoes hepatic metabolism through the fructokinase pathway, bypassing phosphofructokinase regulation. This leads to:

- Rapid ATP depletion

- Increased uric acid production

- Hepatic de novo lipogenesis

- Insulin signaling pathway disruption

Pancreatic function deteriorates over time as beta cells struggle to maintain glucose homeostasis against persistent insulin resistance.

3. Cardiovascular Disease

Cardiovascular disease risk increases substantially with high added sugar consumption. Triglyceride elevation, HDL cholesterol reduction, and systemic inflammation markers rise with chronic sugar overconsumption.

Detailed Biological Mechanisms: Advanced Glycation End products (AGEs) form when reducing sugars react with proteins or lipids. AGEs accumulate in arterial walls, promoting:

- Endothelial dysfunction

- Arterial stiffening

- Inflammatory cytokine release

- Atherosclerotic plaque formation

Blood pressure elevation occurs through multiple mechanisms including sodium retention, sympathetic nervous system activation, and endothelial nitric oxide reduction.

4. Tooth Decay and Oral Health Problems

Oral bacteria, particularly Streptococcus mutans, metabolize dietary sugars into lactic acid. This acid production lowers oral pH, demineralizing tooth enamel and initiating carious lesion formation.

Frequency of sugar exposure matters more than total amount. Frequent snacking on sugary foods maintains acidic oral environment, preventing natural remineralization processes.

5. Mood and Energy Changes

Blood glucose fluctuations from high-sugar meals create energy crashes 2-3 hours post-consumption. Reactive hypoglycemia symptoms include fatigue, irritability, difficulty concentrating, and anxiety.

Dopamine pathway activation in the brain’s reward system responds to sugar consumption, potentially creating behavioral patterns resembling addiction-like responses.

6. Sugar Addiction and Related Psychology

Neurological and Behavioral Basis: Sugar consumption activates the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and nucleus accumbens, core components of the brain’s reward circuitry. Dopamine release patterns mirror those seen with addictive substances, though to lesser degrees.

Emotional Eating: Stress-induced cortisol elevation increases sugar cravings through hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activation. Comfort food consumption provides temporary mood elevation but doesn’t address underlying emotional triggers.

Management Strategies: Cognitive behavioral techniques help identify trigger situations. Mindful eating practices, stress management techniques, and gradual reduction strategies prove more effective than complete elimination approaches.

C. Sugar’s Impact on Special Population Groups

1. Children

Pediatric obesity rates correlate strongly with early-life sugar exposure patterns. Brain development during childhood shows particular sensitivity to dietary influences, with some evidence suggesting high-sugar diets may impact cognitive function and attention span.

Type 2 diabetes in pediatric populations, once rare, now represents a growing clinical concern. Early metabolic programming during childhood establishes long-term health trajectories.

2. Pregnant Women

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) risk increases with high dietary sugar intake during pregnancy. Maternal hyperglycemia affects fetal development, potentially programming offspring for future metabolic disorders.

The intrauterine environment influences fetal pancreatic development, with implications for lifetime diabetes risk in offspring.

3. Elderly Adults

Age-related insulin sensitivity decline makes older adults particularly vulnerable to glucose intolerance. Chronic inflammation associated with high sugar intake may accelerate cognitive decline, with some researchers linking it to Alzheimer’s disease pathology (“Type 3 diabetes”).

Bone health concerns arise as high sugar diets may interfere with calcium absorption and contribute to osteoporosis progression.

4. Individuals with Chronic Diseases

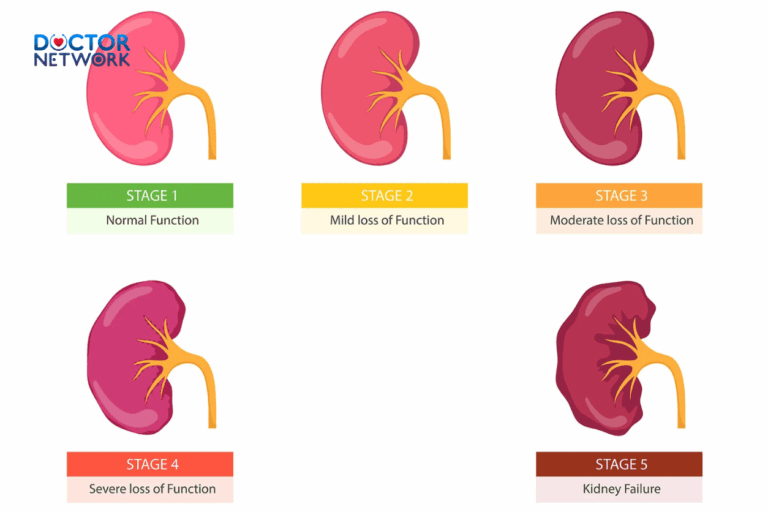

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) progression accelerates with high fructose intake. Kidney disease patients face additional challenges as sugar metabolism byproducts strain already compromised renal function.

Metabolic syndrome components (hypertension, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, abdominal obesity) all worsen with excessive sugar consumption.

V. Hidden Sugars and the Food Industry’s Role

A. Hidden Sugars in Processed Foods

Processed foods frequently contain surprising amounts of hidden sugars, even in products marketed as “healthy.” Popular items with concealed sugar content include:

“Healthy” Foods Containing Hidden Sugars:

- Flavored yogurt: May contain 15-20g added sugars per serving

- Granola bars: Often contain 8-12g added sugars per bar

- Peanut butter: Many brands add 2-4g sugar per serving

- Canned fruit in syrup: Can double natural fruit sugar content

- Condiments: Ketchup, BBQ sauce, salad dressings often contain 3-8g sugar per serving

- Savory soups: Canned varieties may include 5-10g added sugars

Breakfast cereals, energy bars, and sports drinks represent some of the highest sources of added sugars in the typical American diet.

B. Importance of Reading Nutrition Labels

Nutrition Facts labels now require separate listing of “Added Sugars” under total carbohydrates. This regulatory change helps consumers distinguish between naturally occurring sugars and those added during processing.

Alternative Names for Sugar on Labels:

- High fructose corn syrup (HFCS)

- Corn syrup solids

- Agave nectar

- Cane juice/sugar

- Maltose, dextrose, glucose

- Brown rice syrup

- Coconut nectar

- Date syrup

Ingredient lists show components in descending order by weight. When multiple sugar sources appear among the first few ingredients, products likely contain substantial added sugar amounts.

Daily Intake Recommendations from Health Organizations:

| Organization | Daily Recommendation |

|---|---|

| USDA | <10% of total daily calories |

| American Heart Association (Women) | ≤25g (6 tsp) |

| American Heart Association (Men) | ≤37.5g (9 tsp) |

| WHO | <10% of total daily calories (ideally <5%) |

C. The Food Industry’s Role

1. Marketing and Advertising Strategies

Food industry marketing strategies specifically target children through cartoon characters, colorful packaging, and strategic placement in grocery stores. Health claims like “natural,” “organic,” or “made with real fruit” can mislead consumers about actual sugar content.

Social media advertising increasingly targets specific demographics with personalized content promoting high-sugar products during vulnerable moments (late-night snacking, stress periods).

2. Influence on Public Policy

Industry lobbying efforts have historically influenced dietary guidelines and public health policies. Research funding from sugar industry sources has occasionally introduced bias into scientific literature, similar to tactics used by tobacco companies decades earlier.

Public health initiatives like sugar taxes face significant industry opposition, despite evidence supporting their effectiveness in reducing consumption.

3. Challenges and Solutions

Reformulation efforts by manufacturers aim to reduce sugar content while maintaining palatability. Technical challenges include preserving texture, shelf life, and consumer acceptance with lower-sugar formulations.

Alternative sweetener incorporation faces regulatory hurdles, cost considerations, and consumer skepticism about artificial ingredients. Clean label trends drive demand for recognizable ingredient names.

VI. How to Reduce Sugar Consumption

A. General Strategies

1. Choose Whole Foods

Whole foods naturally contain lower sugar concentrations and provide beneficial nutrients absent in processed alternatives. Fresh fruits offer natural sweetness plus fiber, vitamins, and antioxidants that slow sugar absorption and promote satiety.

Whole grains, lean proteins, and vegetables form a dietary foundation that minimizes sugar cravings through stable blood glucose maintenance.

2. Limit Sugar-Sweetened Beverages

Sugar-sweetened beverages contribute the largest single source of added sugars in the American diet. Sodas, sports drinks, energy drinks, and specialty coffee beverages can contain 25-40g sugar per serving.

Alternatives to Sugary Drinks:

- Plain water with lemon/lime slices

- Unsweetened tea and coffee

- Sparkling water with natural fruit flavoring

- Diluted 100% fruit juice (1:1 ratio with water)

3. Cook at Home

Home cooking provides complete control over added sugar content. Homemade salad dressings, sauces, and marinades typically contain a fraction of the sugar found in commercial versions.

Baking modifications can reduce sugar content by 25-30% in most recipes without significantly affecting taste or texture.

4. Use Natural Sweeteners Moderately

Natural flavor enhancers can provide sweetness without added calories:

- Cinnamon: Adds sweetness perception without sugar

- Vanilla extract: Enhances sweet taste in baked goods

- Mashed banana: Natural sweetener in smoothies, oatmeal

- Dates: Whole food sweetener in energy balls, desserts

5. Read Nutrition Labels Carefully

Systematic label reading becomes second nature with practice. Focus on the “Added Sugars” line rather than total sugars, which includes naturally occurring sugars from fruits and dairy products.

Compare similar products to identify lower-sugar options. Many brands offer reduced-sugar versions of popular items.

6. Gradually Reduce Sugar Amount

Gradual reduction allows taste preferences to adapt naturally. Start by reducing coffee/tea sweetener by half, then continue decreasing weekly until eliminated or minimized.

Environmental modifications help reduce consumption: store sugar containers in cabinets rather than countertops, purchase smaller packages, avoid buying high-sugar snacks for home storage.

7. Replace Sweets with Fruit

Fresh fruit satisfies sweet cravings while providing beneficial nutrients. Berries, apple slices, and citrus fruits offer natural sweetness plus fiber that helps regulate blood sugar response.

Frozen fruit creates natural “ice cream” alternatives when blended, providing dessert satisfaction with nutritional benefits.

B. Specific Dietary Methods for Sugar Reduction

1. Low-Carb and Keto Diets

Low-carbohydrate diets drastically reduce sugar intake by limiting total carbohydrate consumption to 50-150g daily. Ketogenic approaches restrict carbs to <50g daily, forcing metabolic shift to fat utilization.

These dietary patterns often produce rapid weight loss, improved insulin sensitivity, and reduced sugar cravings within weeks of implementation.

2. Paleo Diet

The Paleolithic dietary approach eliminates processed foods entirely, focusing on whole foods available to pre-agricultural humans. This naturally excludes added sugars while allowing moderate amounts of natural sugars from fruits.

Emphasis on protein, healthy fats, and vegetables provides steady energy without blood sugar fluctuations associated with high-sugar diets.

3. Sugar “Detox” Programs

Sugar detoxification programs typically involve 7-30 day periods of complete added sugar elimination. These approaches aim to reset taste preferences and break psychological dependencies on sweet foods.

Success rates improve when combined with meal planning, stress management techniques, and social support systems.

C. Cultural and Social Aspects of Sugar

1. Sugar in Traditional Cuisine

Cultural celebrations worldwide feature sugar-centric foods: wedding cakes, holiday cookies, religious festival sweets. These traditions create emotional connections between sugar consumption and positive social experiences.

Balancing cultural preservation with health considerations requires thoughtful approaches that honor traditions while promoting moderation.

2. Social Norms

Social settings often revolve around food sharing, frequently involving high-sugar items. Office birthday celebrations, social gatherings, and restaurant dining create peer pressure to consume sugary foods.

Developing strategies for social situations helps maintain dietary goals without social isolation.

D. Historical Context of Sugar Consumption

1. The Rise of Sugar

Sugar transformed from a rare luxury item to dietary staple over the past 300 years. Colonial sugar trade drove economic development but relied on enslaved labor, creating a complex historical legacy.

Industrialization made refined sugar widely available and affordable, contributing to dramatic consumption increases throughout the 20th century. Per capita consumption peaked in the 1970s-1980s before declining to current levels.

VII. Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How many calories are in 1 teaspoon of sugar? One teaspoon of granulated white sugar contains 16 calories. This equals 4.2 grams of sugar and 4.2 grams of total carbohydrates.

Is brown sugar healthier than white sugar? Brown sugar and white sugar have virtually identical caloric content (16 calories per teaspoon) and nutritional profiles. Molasses content in brown sugar provides negligible amounts of minerals like calcium and iron, insufficient to create meaningful health advantages.

Does honey have fewer calories than sugar? Honey actually contains more calories per teaspoon (21 vs 16) compared to table sugar. However, honey’s higher sweetness intensity may allow smaller quantities for equivalent sweetness perception. Honey also provides trace antioxidants and antimicrobial compounds absent in refined sugar.

What happens if I eat too much sugar in one day? Acute high sugar consumption can cause energy spikes followed by crashes, resulting in fatigue, mood swings, and increased hunger. Long-term excessive intake elevates risks of obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and dental problems.

Are non-caloric sweeteners safe? FDA-approved artificial sweeteners like stevia, erythritol, monk fruit, sucralose, and aspartame undergo extensive safety testing. Current evidence supports their safety when consumed within Acceptable Daily Intake levels established by regulatory agencies.

Can you burn off calories from sugar? Physical activity burns calories from all sources, including sugar. A 16-calorie teaspoon of sugar requires approximately:

- 4 minutes of brisk walking

- 2 minutes of jogging

- 1.5 minutes of jumping rope

- 3 minutes of cycling

What are some low-sugar snack options?

Healthy Low-Sugar Snack Options:

- Raw vegetables with hummus

- Greek yogurt with berries

- Nuts and seeds

- Hard-boiled eggs

- Cheese cubes with apple slices

- Air-popped popcorn

- Avocado toast on whole grain bread

VIII. Conclusion

Understanding the caloric content of dietary sugars empowers informed nutritional decisions that compound into significant health improvements over time. The seemingly small 16 calories in one teaspoon of sugar becomes substantial when multiplied across daily consumption patterns from multiple sources.

Distinguishing between naturally occurring sugars in whole foods versus added sugars in processed products represents crucial nutritional literacy. Natural sugars from fruits and dairy products arrive packaged with beneficial nutrients, fiber, and compounds that moderate their metabolic impact. Added sugars, conversely, provide energy without nutritional cofactors necessary for optimal health.

Sustainable sugar reduction requires gradual lifestyle modifications rather than dramatic dietary overhauls. Reading nutrition labels, choosing whole foods, cooking at home, and mindful portion control create lasting behavioral changes. These practices, combined with regular physical activity and stress management, form comprehensive approaches to optimal health maintenance.

The food industry continues evolving toward lower-sugar formulations in response to consumer demand and regulatory pressure. However, individual vigilance remains essential for navigating marketing claims and identifying hidden sugar sources in processed foods.

The 5 most frequently asked questions about the topic “how many calories in a teaspoon of sugar” along with detailed answers:

1. How many calories are in a teaspoon of sugar?

A teaspoon of granulated sugar typically weighs about 4 grams and contains approximately 16 calories. This is because each gram of carbohydrate provides 4 calories, so 4 grams × 4 calories/gram = 16 calories.

2. Does brown sugar have more calories than white sugar?

Brown sugar and white sugar have very similar calorie content, around 16-17 calories per teaspoon (4 grams). The main difference is that brown sugar contains a small amount of molasses, which gives it its color and flavor, but nutritionally, they are almost the same.

3. Do natural sweeteners like honey or agave syrup have more calories?

Natural sweeteners such as honey and agave syrup are denser, so a teaspoon contains more calories than white sugar. For example, one teaspoon of honey contains about 20-21 calories, and agave syrup about 20 calories, which is higher than the 16 calories in white sugar.

4. Why should sugar intake be limited?

Sugar provides “empty calories,” meaning it supplies energy without vitamins or minerals. Excessive sugar consumption can lead to weight gain, type 2 diabetes, tooth decay, fatty liver disease, inflammation, heart disease, and other health issues.

5. How much sugar should be consumed daily?

Health organizations recommend:

Men should limit added sugar intake to no more than 37.5 grams (about 9 teaspoons) per day.

Women should limit added sugar intake to no more than 25 grams (about 6 teaspoons) per day.

Women should limit added sugar intake to no more than 25 grams (about 6 teaspoons) per day.

The World Health Organization (WHO) suggests that “free sugars” (added sugars, honey, syrups) should make up less than 5% of total daily calories, roughly 25 grams.

References

1. The Primary Scientific Evidence: Nutritional Data from Government Agencies

The most direct and authoritative evidence comes from national nutritional databases, which are compiled based on extensive laboratory analysis (calorimetry) and food composition data.

Evidence/Finding:

Sugar (sucrose) is a carbohydrate, and pure carbohydrates provide approximately 4 kilocalories (kcal) of energy per gram.

Source 1: U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) FoodData Central

Origin/Author: U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), a United States federal executive department responsible for developing and executing federal laws related to farming, forestry, rural economic development, and food.

Details: The USDA’s FoodData Central is the main nutrient data source in the United States. It lists granulated sugar as containing approximately 3.87 to 4 calories per gram. The standard value used in nutrition labeling is 4 calories per gram.

Citation: In the USDA FoodData Central database, you can look up “Sugar, granulated” (FDC ID: 169642). The data confirms that 100 grams of sugar contains roughly 387 calories, which is 3.87 calories per gram.

Evidence/Finding:

A standard U.S. teaspoon of granulated sugar weighs approximately 4.2 grams.

Source 2: U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Nutrient Database

Origin/Author: U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA).

Details: The USDA provides standard reference conversions for common household measurements. They define a level teaspoon of granulated white sugar as weighing 4.2 grams.

Citation: This is a standard conversion value used throughout the USDA’s resources and referenced by nutritionists and dietitians globally.

Calculation Based on Primary Evidence:

Grams per teaspoon × Calories per gram = Total calories per teaspoon

4.2 grams × 4 calories/gram = 16.8 calories

This is why the number is commonly rounded down to 16 calories for simplicity and public communication.

2. Related Scientific Research & Public Health Guidelines

While there are no “studies” specifically designed to discover the calories in a teaspoon of sugar (as this is fundamental nutritional science), major health organizations conduct extensive research and meta-analyses that use this data to form public health recommendations about sugar consumption. These guidelines are a form of scientific consensus.

Research/Guideline 1: American Heart Association (AHA) Recommendation on Added Sugars

Origin/Author: The American Heart Association (AHA), a U.S. non-profit organization that funds cardiovascular medical research and educates consumers on healthy living.

Details: The AHA uses the standard caloric value of sugar to create daily intake limits to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease, obesity, and other health problems. Their recommendations are based on a large body of scientific research linking high sugar intake to negative health outcomes.

For Men: No more than 150 calories per day from added sugar (equivalent to 36 grams or 9 teaspoons).

For Women: No more than 100 calories per day from added sugar (equivalent to 24 grams or 6 teaspoons).

Citation: “Dietary Sugars Intake and Cardiovascular Health,” a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Published in the journal Circulation (2009). Johnson, R. K., Appel, L. J., Brands, M., et al.

Research/Guideline 2: World Health Organization (WHO) Guideline on Sugars Intake

Origin/Author: The World Health Organization (WHO), a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for international public health.

Details: The WHO’s recommendations are based on a systematic review of scientific evidence linking the consumption of “free sugars” (which includes sugar added to foods and drinks) to body weight and dental caries.

The WHO strongly recommends reducing the intake of free sugars to less than 10% of total daily energy intake.

They also provide a “conditional recommendation” for a further reduction to below 5% of total energy intake for additional health benefits.

Citation: “Guideline: Sugars intake for adults and children.” (2015). World Health Organization, Geneva. This document synthesizes evidence from numerous scientific studies.

Kiểm Duyệt Nội Dung

More than 10 years of marketing communications experience in the medical and health field.

Successfully deployed marketing communication activities, content development and social networking channels for hospital partners, clinics, doctors and medical professionals across the country.

More than 6 years of experience in organizing and producing leading prestigious medical programs in Vietnam, in collaboration with Ho Chi Minh City Television (HTV). Typical programs include Nhật Ký Blouse Trắng, Bác Sĩ Nói Gì, Alo Bác Sĩ Nghe, Nhật Ký Hạnh Phúc, Vui Khỏe Cùng Con, Bác Sỹ Mẹ, v.v.

Comprehensive cooperation with hundreds of hospitals and clinics, thousands of doctors and medical experts to join hands in building a medical content and service platform on the Doctor Network application.