Discover “why palliative care is bad“: widespread misconceptions, limited access, inconsistent quality, and ethical dilemmas plague this approach. Explore critical challenges and alternative options for serious illness management.

Palliative care presents a paradoxical situation in modern healthcare: while designed to provide compassionate symptom management and improve quality of life for those with serious illnesses, it faces significant criticism and implementation challenges. As a specialized medical approach focused on relieving suffering and enhancing wellbeing for patients facing life-threatening conditions, palliative care aims to address physical symptoms while providing psychological, emotional, and spiritual support. By understanding these limitations, healthcare providers, patients, and families can better navigate this complex landscape and advocate for necessary improvements in end-of-life and serious illness care.

Understanding Palliative Care

Palliative care fundamentally differs from traditional medical approaches by focusing on quality of life rather than curative outcomes alone. The World Health Organization defines palliative care as “an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial and spiritual.” Unlike hospice care, which typically begins when curative treatment stops, palliative care can commence upon diagnosis and continue alongside disease-modifying therapies.

The core principles of comprehensive palliative care include:

- Symptom management: Addressing pain, nausea, breathlessness, fatigue, and other distressing symptoms

- Holistic support: Providing emotional, psychological, and spiritual care

- Communication facilitation: Enhancing decision-making processes between patients, families, and healthcare teams

- Care coordination: Ensuring seamless transitions between different healthcare settings

- Family assistance: Supporting caregivers throughout the illness trajectory and bereavement

Despite these noble intentions, the implementation and delivery of palliative care services face numerous challenges that can diminish their effectiveness and contribute to negative perceptions.

Why Palliative Care is Bad

Criticisms and Downsides: Why Palliative Care Can Be Viewed Negatively

Misconceptions and Lack of Awareness

Widespread misconceptions about palliative care significantly hamper its acceptance and utilization in clinical settings. The most pervasive misunderstanding equates palliative care with hospice care or perceives it exclusively as end-of-life care, creating immediate resistance among patients and families. Dr. Christophe Garon, Director of Integrated Oncology at Memorial Research Center, explains: “When I mention palliative care to my patients, many immediately think I’m telling them to give up hope, when in reality, I’m offering additional support alongside their cancer treatments.”

This perception that palliative care means “giving up” on active or curative treatment represents a fundamental barrier to early implementation. Studies published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology demonstrate that early palliative care intervention can actually extend survival in some cancer patients, contradicting the notion that it accelerates death or replaces disease-modifying therapies.

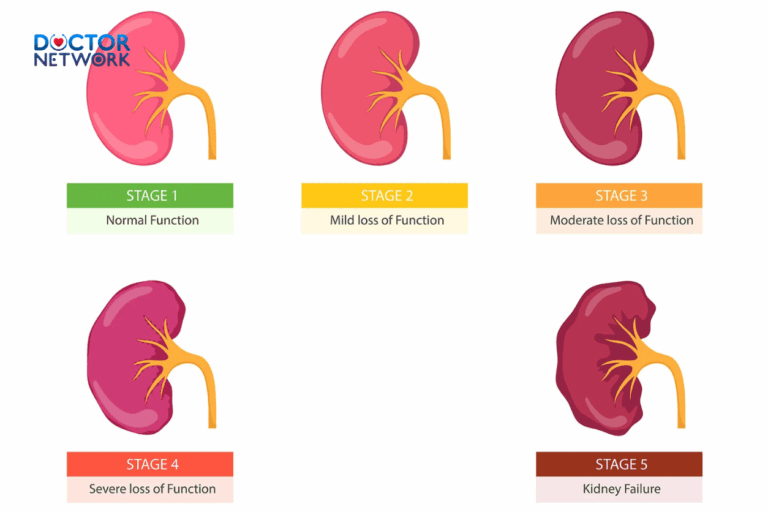

Another limiting belief restricts palliative care to cancer patients, ignoring its potential benefits for individuals with heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, kidney failure, dementia, and other serious conditions. The terminology itself creates confusion, with terms like “supportive care,” “comfort care,” and “symptom management” sometimes used interchangeably, further muddying public understanding.

Healthcare providers themselves often harbor misinformation about palliative care’s scope and potential benefits. A survey conducted by the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine (AAHPM) revealed that 42% of primary care physicians incorrectly believed palliative care required discontinuation of curative treatments. This lack of awareness among medical professionals perpetuates the cycle of misunderstanding and underutilization.

Access, Availability, and Financial Barriers

Geographic and demographic disparities severely limit palliative care accessibility, creating a healthcare divide that disproportionately affects vulnerable populations. Urban concentration of specialized services means patients in rural or remote areas often face prohibitive travel distances to receive appropriate care. The National Palliative Care Registry reports that while 90% of hospitals with over 300 beds offer palliative care programs, only 56% of smaller hospitals provide these services.

| Palliative Care Availability by Hospital Size | Percentage with Programs |

|---|---|

| Large hospitals (300+ beds) | 90% |

| Medium hospitals (100-299 beds) | 68% |

| Small hospitals (<100 beds) | 56% |

Healthcare infrastructure significantly influences service availability, with disparities particularly pronounced in developing nations and underserved communities. Even within developed healthcare systems, socioeconomic factors create inequitable access patterns. Research from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) indicates that minority populations and those with lower educational attainment receive referrals to palliative care services at substantially lower rates.

Financial considerations represent another formidable barrier. Insurance coverage for palliative care varies widely, with inconsistent reimbursement policies creating confusion for providers and patients alike. Medicare covers hospice care but has limitations on concurrent palliative services with curative treatments. Many private insurers offer incomplete coverage, leaving substantial out-of-pocket costs for families already burdened by medical expenses.

Shining Light Hospice’s financial counselor, Parth Khanna, notes: “Families frequently discover that while basic palliative consultations may be covered, specialized interventions, home adaptations, and complementary therapies often require significant personal expenditure.” The absence of comprehensive financial assistance programs exacerbates this burden, leaving many patients to choose between financial stability and appropriate symptom management.

A significant content gap exists regarding practical guidance for patients and families navigating the complex financial landscape of palliative care. Resources providing clear explanation of insurance benefits, negotiation strategies with providers, and available financial assistance programs remain insufficient, leaving families to navigate these challenges during an already difficult time.

Communication Issues

Effective communication represents the cornerstone of quality palliative care, yet communication breakdowns consistently emerge as a primary source of patient and family dissatisfaction. Healthcare providers often struggle to clearly articulate palliative care’s role, benefits, and relationship to other treatment modalities. This communication deficit leads to misinterpretation by patients and families, who may perceive palliative care recommendations as abandonment rather than supportive intervention.

Explaining complex concepts like a “good death” presents particular challenges, especially when balancing conflicting needs among family members. Studies published in the Journal of Palliative Medicine indicate that negative feedback regarding palliative care experiences predominantly relates to communication issues and perceived physician attitudes rather than technical aspects of care delivery.

Common communication failures include:

- Inadequate explanation of prognosis and treatment options

- Insufficient time allocated for difficult conversations

- Failure to address cultural and religious perspectives on illness and death

- Inconsistent messaging between different healthcare team members

- Limited involvement of patients in decision-making processes

Research reveals a striking discordance between physician perception of communication quality and patient experience. While 73% of physicians believe they adequately explain palliative care options, only 29% of patients report receiving comprehensive information about available services and approaches.

Current literature contains a notable content gap regarding specific, evidence-based communication strategies for providers beyond general recommendations. Detailed frameworks for delivering difficult news, managing family conflicts, and addressing sensitive topics like prognosis uncertainty would significantly enhance care quality but remain underdeveloped in clinical guidelines.

Quality and Consistency of Care

The absence of universal standards in palliative care delivery results in troubling variability in service quality across different providers and institutions. Unlike many medical specialties with established protocols, palliative care practices often depend heavily on individual practitioner judgment and institutional culture. This inconsistency creates a “lottery” effect where patient experiences vary dramatically based on provider and location rather than clinical needs.

Pain management exemplifies this variability, with documented discrepancies in assessment methods, medication selection, and dosing protocols. A multicenter study by the Journal of Pain and Symptom Management found three-fold variations in opioid prescribing patterns among palliative care teams treating comparable conditions, suggesting significant inconsistency in approach.

Patient satisfaction metrics reflect these quality concerns. Hospital-based palliative care consistently receives lower satisfaction ratings compared to home-based services, with particular criticism regarding coordination between services and delays in symptom management. A nationwide survey conducted by the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO) found that only 62% of respondents rated hospital-based palliative care as “excellent” compared to 84% for home-based services.

| Palliative Care Setting | “Excellent” Rating | Common Complaints |

|---|---|---|

| Hospital-based | 62% | Poor coordination, delayed response to symptoms |

| Home-based | 84% | Limited availability, caregiver strain |

| Outpatient clinic | 76% | Transportation difficulties, fragmented care |

The research literature reveals significant gaps concerning specific strategies and initiatives needed to establish uniform quality guidelines across diverse care settings. Additionally, limited guidance exists on managing challenging medication side effects beyond opioid protocols, creating uncertainty in addressing complex symptom clusters like fatigue, anorexia, and cognitive impairment.

Ethical Considerations and Dilemmas

Palliative care encounters uniquely complex ethical territory, navigating the tension between symptom relief and potential side effects while balancing patient autonomy with medical recommendations. End-of-life decision making presents particularly challenging dilemmas regarding the continuation or withdrawal of treatments like mechanical ventilation, artificial nutrition, and cardiac supportive measures. These decisions grow increasingly complex when patients cannot express their preferences and surrogates must interpret previous statements about quality of life.

Cultural and religious considerations add another layer of complexity. Different belief systems maintain varying perspectives on death, pain management, medical interventions, and family involvement in healthcare decisions. For example, some religious traditions view suffering as spiritually meaningful, potentially conflicting with palliative care’s focus on symptom management. Others maintain restrictions on certain medications or interventions, limiting available options.

Medication regimens present their own ethical challenges, particularly when treatments for pain or anxiety may result in sedation or altered consciousness. This tension between symptom control and cognitive presence creates difficult trade-offs for patients and families, especially near the end of life when meaningful interaction becomes increasingly precious.

Five ethical principles typically guide palliative care decisions:

- Autonomy: Respecting patients’ right to make informed decisions

- Beneficence: Acting in patients’ best interests

- Non-maleficence: Avoiding unnecessary harm

- Justice: Fair distribution of resources and access

- Dignity: Preserving patient worth and self-respect

Unfortunately, current literature lacks adequate concrete examples and detailed case studies illustrating specific ethical dilemmas in practice. Additionally, limited exploration exists regarding how specific cultural or religious beliefs impact palliative care decisions and delivery across different populations, representing a significant perspective gap in clinical guidance.

Emotional and Psychological Impact

The psychological toll of serious illness extends far beyond physical symptoms, creating emotional challenges that palliative care aims to address but often inadequately manages. Depression affects approximately 25-77% of palliative care patients, while anxiety disorders occur in 25-46%, according to comprehensive reviews in the Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. Despite this prevalence, psychological support frequently represents an afterthought rather than a core component of care plans.

Palliative care theoretically provides psychological support through counseling, therapy, social work, and chaplaincy services. However, implementation varies widely, with mental health professionals often incorporated inconsistently into interdisciplinary teams. A survey of 220 palliative care programs found that only 42% included dedicated psychological services, while 68% reported inadequate mental health screening protocols.

The perception that a condition is untreatable can foster an environment of hopelessness, contributing to psychological distress. Patients commonly report feelings of abandonment when transitioned to palliative care, particularly if they perceive the change as healthcare providers “giving up” on their treatment. This perception, while often inaccurate, significantly impacts psychological wellbeing and treatment engagement.

Anxiety represents another common psychological challenge, manifesting through fear of pain, concern about being a burden, uncertainty about the future, and existential distress. Effective palliative care must address these concerns directly, yet psychological interventions often receive less attention than physical symptom management.

Impact on Families and Caregivers

Family caregivers shoulder extraordinary burdens when supporting seriously ill loved ones, experiencing physical, emotional, financial, and social consequences that often receive insufficient attention. While palliative care philosophy acknowledges the importance of supporting families, implementation of comprehensive caregiver assistance programs remains inconsistent across healthcare settings.

The caregiver experience includes multiple challenges:

- Physical strain: Tasks like lifting, bathing, and medication management

- Emotional distress: Anticipatory grief, anxiety, depression

- Financial impact: Lost wages, medical expenses, household adaptations

- Social isolation: Reduced participation in community activities

- Role adjustments: Changes in family dynamics and responsibilities

Research published in the Journal of Pain and Symptom Management indicates that 40-70% of family caregivers experience clinically significant depression during the caregiving period, while 25-50% meet diagnostic criteria for anxiety disorders. These psychological impacts often persist beyond the patient’s death, affecting long-term mental health outcomes.

Caregiver needs sometimes compete with patient priorities, creating tension in care planning. For example, family members may advocate for more aggressive pain control than patients desire, or request treatments that patients have declined. These discrepancies create ethical dilemmas for healthcare providers attempting to balance respect for patient autonomy with family concerns.

Current literature contains significant gaps regarding specific interventions and support systems available for caregivers. While general recommendations exist, detailed protocols for caregiver assessment, education, and support remain underdeveloped, reflecting the persistent focus on patients rather than the entire affected family system.

Workforce, Training, and Research Barriers

The global shortage of healthcare professionals trained in palliative care principles creates significant service gaps that undermine quality and accessibility. The World Health Organization estimates that 86% of global palliative care needs remain unmet due to workforce limitations, with particularly severe shortages in developing regions. Even in developed healthcare systems, specialist availability remains insufficient to meet growing demand.

General practitioners and non-specialist providers frequently lack adequate training in pain management, communication skills, and psychosocial support necessary for effective palliative care delivery. A survey of medical schools found that only 18% required dedicated palliative care rotations, while 42% offered no formal curriculum in pain management beyond basic pharmacology.

Research funding disparities further hamper progress, with palliative care receiving disproportionately small allocations compared to prevention and cure-focused initiatives. Cancer research provides a stark example, with less than 0.3% of cancer research funding directed toward palliative interventions despite the significant symptom burden associated with the disease.

| Research Focus | Percentage of Cancer Research Funding |

|---|---|

| Prevention | 33.1% |

| Early detection | 14.8% |

| Treatment | 46.1% |

| Survivorship | 5.7% |

| Palliative care | 0.3% |

Multiple barriers impede palliative care research:

- Limited funding sources and lower priority in grant allocations

- Institutional capacity constraints for specialized research

- Shortage of trained researchers in the field

- Methodological challenges with vulnerable populations

- High participant attrition rates due to declining health

- Complex ethical considerations in study design and implementation

A significant perspective missing from current literature concerns the challenges faced by healthcare providers themselves. Limited exploration exists regarding provider burnout, moral distress, ethical conflicts, and the emotional toll of continuous exposure to suffering and death. Understanding these provider experiences represents a crucial aspect of improving system-wide care quality.

Areas for Improvement and Addressing Criticisms

Addressing palliative care’s shortcomings requires multifaceted approaches focusing on education, communication, accessibility, and quality standardization. Public awareness campaigns represent a crucial first step, utilizing personal stories and testimonials to dispel myths and explain benefits to both providers and the general population. Organizations like Get Palliative Care have pioneered multimedia approaches combining traditional advertising with social media outreach to reach diverse audiences.

Improving communication between healthcare teams, patients, and families requires systematic changes in medical education and institutional culture. Evidence-based communication techniques like motivational interviewing and shared decision-making models demonstrate improved outcomes in challenging conversations about prognosis and treatment options. Structured communication protocols such as SPIKES (Setting, Perception, Invitation, Knowledge, Empathy, Strategy) provide frameworks for delivering difficult news while maintaining therapeutic relationships.

Patient-centered care approaches address many quality concerns by tailoring interventions to individual needs, values, and goals rather than applying standardized protocols. Advance care planning tools facilitate this personalization by documenting preferences before crisis situations arise. Research demonstrates that patients with completed advance directives experience greater alignment between desired and received care compared to those without such documentation.

Research initiatives addressing current knowledge gaps include the MORECare project, which provides specific methodological guidance for palliative care studies. Funding programs through organizations like the NIHR and NCRI have created dedicated streams for palliative care research, addressing historical funding imbalances. These initiatives aim to build the evidence base necessary for developing standardized quality metrics and best practice guidelines.

Geographic accessibility barriers require innovative service delivery models. Studies examining 24-hour community care programs demonstrate reduced hospital admissions and emergency department visits compared to standard services. Telemedicine initiatives show particular promise for rural and underserved areas, providing specialist consultation without requiring patient travel. Home-based palliative care programs consistently demonstrate improved outcomes including higher patient satisfaction, reduced healthcare costs, and decreased caregiver burden compared to institution-based alternatives.

Exploring Alternatives

Some patients explore complementary approaches alongside or instead of conventional palliative care services. Complementary therapies including acupuncture, massage, and herbal treatments demonstrate varying evidence levels for symptom management. Meta-analyses indicate moderate evidence supporting acupuncture for cancer-related pain and massage therapy for anxiety reduction, while evidence for herbal interventions remains more limited.

Integrative oncology represents another alternative approach, combining conventional treatment with holistic practices focused on physical and emotional wellbeing. Programs at major cancer centers increasingly incorporate meditation, yoga, nutritional counseling, and art therapy alongside medical interventions. Patient-reported outcomes suggest improvements in quality of life metrics, though further research is needed regarding impact on disease progression and survival.

Clinical trials offer additional options for patients seeking innovative approaches to symptom management or disease modification. Participation provides access to cutting-edge therapies while contributing to scientific knowledge. However, eligibility criteria often exclude patients with advanced disease or multiple comorbidities, limiting accessibility for many palliative care recipients.

Conclusion

Palliative care, despite its criticisms and implementation challenges, remains an essential component of comprehensive healthcare for those facing serious illness. The identified shortcomings—misconceptions, access barriers, communication breakdowns, quality inconsistencies, ethical dilemmas, and insufficient family support—represent opportunities for improvement rather than reasons for abandonment. By addressing these issues through education, enhanced communication, expanded research, and patient-centered approaches, healthcare systems can realize palliative care’s full potential to improve quality of life for patients and families navigating serious illness.

Progress requires collaborative effort from healthcare institutions, professional organizations, funding bodies, and advocacy groups. The ultimate goal remains ensuring that palliative care is recognized, properly implemented, and effectively utilized to alleviate suffering and enhance wellbeing throughout the illness trajectory. Patients and families facing serious illness deserve compassionate, comprehensive care that addresses all dimensions of their experience—physical, emotional, social, and spiritual.

For those navigating serious illness, open discussion with medical professionals about all available options, including both conventional palliative care and complementary approaches, represents the best path forward. Resources available through organizations like the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine (AAHPM), National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO), World Health Organization (WHO), and Get Palliative Care provide valuable information for making informed healthcare decisions during challenging times.

Frequently Asked Questions about

1. Why do some people think palliative care causes patients to die sooner?

Answer:

This is a common misconception. In reality, palliative care does not hasten death. Instead, it focuses on relieving pain and symptoms to improve quality of life. Numerous studies have shown that patients receiving palliative care may actually live longer or have better overall well-being compared to those who do not receive it. Palliative care is about comfort and support, not ending life prematurely.

2. Is palliative care only for patients who are terminally ill or in the final stages of cancer?

Answer:

No, palliative care is not limited to terminal cancer patients. It is appropriate for anyone with serious chronic illnesses such as heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), kidney failure, neurological diseases, and more. It can be provided at any stage of illness to help manage symptoms and improve quality of life.

3. Does palliative care mean giving up on curative treatment?

Answer:

Many people mistakenly believe that choosing palliative care means stopping all curative treatments. However, palliative care can be provided alongside treatments aimed at curing or controlling the disease, such as chemotherapy, surgery, or dialysis. The goal is to support the patient’s comfort and well-being throughout their treatment journey.

4. Does palliative care make patients lose control or become dependent on others?

Answer:

Palliative care emphasizes patient autonomy and involves patients and their families in care decisions. It does not take away control but rather supports patients in making informed choices about their care. The approach respects the patient’s wishes and helps maintain as much independence as possible.

5. Is palliative care just about managing pain?

Answer:

While pain management is a key component, palliative care is much broader. It addresses a wide range of physical symptoms (like nausea, breathlessness, fatigue), as well as psychological, social, and spiritual needs. It aims to improve overall quality of life for patients and provide support for their families.

Topic: Misconceptions and Negative Connotations of the Term “Palliative Care”

Issue: The term “palliative care” itself can be a barrier due to negative associations.

Study: Fadul, N., Elsayem, A., Palmer, J. L., Del Fabbro, E., Swint, K., Li, Z., … & Bruera, E. (2009). “Supportive versus palliative care: what’s in a name?: a survey of medical oncologists and midlevel providers at a comprehensive cancer center.” Cancer, 115(9), 2013-2021.

Summary: This study found that healthcare providers sometimes preferred the term “supportive care” over “palliative care” because the latter was perceived more negatively by patients and families, potentially delaying or preventing access.

Link (Abstract/Access): https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19260074/ or https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.24204

Topic: Detriment of Late Referral (Highlighting the problem of not getting it, or getting it too late)

Issue: When palliative care is introduced very late, its potential benefits are severely limited, which can lead to a negative experience or perception of its effectiveness.

Study: Temel, J. S., Greer, J. A., Muzikansky, A., Gallagher, E. R., Admane, S., Jackson, V. A., … & Lynch, T. J. (2010). “Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer.” New England Journal of Medicine, 363(8), 733-742.

Summary: This landmark study demonstrated significant benefits (better quality of life, less depression, longer median survival) for patients receiving early palliative care. By implication, not receiving it early, or receiving it very late, means missing out on these benefits, which could be perceived as a failure or a “bad” outcome due to delay.

Link (Abstract/Access): https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1000678

Topic: Barriers to Access and Integration (Systemic Failures)

Issue: Lack of access, insufficient resources, or poor integration into standard care can lead to patients not receiving appropriate palliative care, resulting in unmet needs and suffering.

Source: World Health Organization (WHO). Various reports and publications on palliative care access. For instance, the “Global Atlas of Palliative Care.”

Summary: WHO consistently highlights that a vast majority of people globally who need palliative care do not receive it. This lack of access due to systemic issues (funding, policy, training) leads to immense preventable suffering, which is a “bad” outcome stemming from the absence or inadequacy of services, not the concept of palliative care itself.

Link (General WHO Palliative Care Page): https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care

(You can find links to specific reports like the Global Atlas from this page or by searching “WHO Global Atlas of Palliative Care”).

Kiểm Duyệt Nội Dung

More than 10 years of marketing communications experience in the medical and health field.

Successfully deployed marketing communication activities, content development and social networking channels for hospital partners, clinics, doctors and medical professionals across the country.

More than 6 years of experience in organizing and producing leading prestigious medical programs in Vietnam, in collaboration with Ho Chi Minh City Television (HTV). Typical programs include Nhật Ký Blouse Trắng, Bác Sĩ Nói Gì, Alo Bác Sĩ Nghe, Nhật Ký Hạnh Phúc, Vui Khỏe Cùng Con, Bác Sỹ Mẹ, v.v.

Comprehensive cooperation with hundreds of hospitals and clinics, thousands of doctors and medical experts to join hands in building a medical content and service platform on the Doctor Network application.